Monday, July 31, 2006

Burning Empires: From Inception to Finished Product (Part IV)

Editing Phase I (March-April)

As we moved into the seventh month working on the Burning Empires project, I was deep in my editing pass. We had gotten to the point where we had established a rolling sequence. There was enough material to edit that Luke was working and redrafting ahead of the sections I was working on. As Luke received my edits, he'd input them and send the section to Rich, who would then take his pass. Once the section was in Rich's hands, Luke couldn't touch it.

"The hardest part was keeping my hands off the material that Rich was working on. That's where the process becomes counter-productive. I can't touch stuff that's with an editor or copy editor, even if I see a mistake! I’ve got concentrate on other stuff and hope the editors do their job."

It was also in this period that we decided the Alien Life-Form Burner would use a similar process and mechanics to the Technology Burner. With that decision in hand, Luke wrote the Alien Life-Form Burner and Playing the Game section, and heavily revised the Technology Burner based on the feedback from our outside playtests.

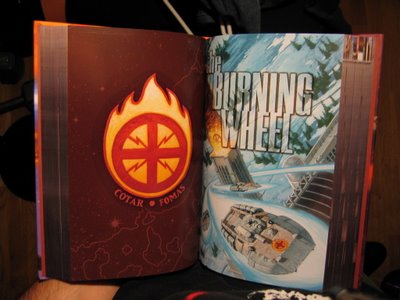

Luke also began an intensive, month-long conversation with Jordan Whorley on the background art and concepts during this period, as they sought to hammer out the layout concept for the book. They had begun with a very different concept from the eventual look of the book, one that was much more like Burning Wheel, but they just couldn't seem to get it right. But as Luke started going through Chris' sketchbooks, and the color plates started coming in, Luke settled on his concept, a sort of "future book from the past."

"The sketches would be the author's own illustrations in his future-past book. The color pics were from the book's archive. It's never explicitly stated anywhere that this is the case, but that's the concept I had in the back of my mine as I settled in to do the layout."

Once they settled on the concept, it only took Jordan a few days to put together the page border and the various markers that served as tabs and would allow the reader to know where he was in the book. Jordan even included a very fine grid that would underlay each page to hint at a screen.

The Art Comes Through (March-April)

While the editing phase was gearing up, preproduction for the art was also underway.

Black & White Part I

It was time to deal with the sketchbooks Chris had sent us in February. Luke and Drozdal spent a fair amount of time researching scanners. Chris' sketchbooks were hardbacks, and he had drawn into the spine on quite a few of the pages.

"We tried to find a book scanner specifically designed to accommodate for the spine bend. There was only one reasonably priced model. Everything else was tens of thousands of dollars, so we had to make do."

Luke, Drozdal and Alexander then proceeded to dig through the sketchbooks, noting which pieces we wanted and which pieces we didn't need. Once they had flagged everything, Dro scanned them all.

"He did several hundred scans in just a few days. It was pretty remarkable. Then Dro and I cleaned up the grayscales—which can get pretty ugly if you don't clean them up—and began to crop out all the elements from the full pages scanned. We cropped heads, weapons, vehicles, characters, but I also kept the full pages in reserve in case I liked a detail and wanted to see what else was going on in that page. This process took a couple of weeks. We had these done before Jordan had delivered his finals and before Chris had provided the color."

Color Part I

On the color art front, the color plates from Dark Horse, mostly covers, arrived in March. Meanwhile, Chris supplied a list of all the originals he still had in his possession. Armed with the list, Luke and Drozdal began combing through the comics to correlate Chris' list with the pages and determine what we needed from the pieces he had available. They also compiled a list of the art we wanted that we would have to scan from the comics themselves.

Luke then passed the list on to Chris so he could begin scanning all the originals in his possession and burn them onto CDs. It took Chris about three weeks to scan all the art and send it our way. Luke rode him pretty hard through the whole period. We all recognized that it was a potential deadline killer if he took too long. We were sunk if he didn't provide the art in time.

As soon as he got his hands on the CDs, Luke sorted the images into three categories: unusable, usable in parts, and full page. The 'unusable' images were those that chopped up the action too much, or, based on a closer look, didn't fit the chapter they had initially been intended for—though some of the unusables did end up in the book in other contexts afterall. The 'unusable in parts' images were those in which the pages would be taken apart and the individual components would be used separately. And the 'full page' images were those images that would be used 'as is.'

Luke color coded each category for easier reference. He then proceeded to do some basic color correction and begin cropping down the usable in parts pieces by chapters (i.e., images intended for the Firefight chapter, images intended for the Duel of Wits chapter, etc.). Unfortunately, the images were so large at this point that Luke rapidly ran out of disk space. We had to run over to CompUSA one afternoon to pick up a new 300GB internal drive in order to accommodate the project.

"This process was a lot (a lot!) of work, but it was necessary. I had to dig into the material and get a feel for it. Doing cropping and color correction is a great way to become intimate with the artwork, especially when you're doing a lot of it.."

Luke also began negotiating with Chris about the book's cover toward the end of March. They had a very long conversation about it. Luke pitched an idea for a sort of Bayeux Tapestry of the Iron Empires, but Chris backed him down and got him to agree to something simpler. Luke though, insisted that it still tell a story. They agreed upon a concept.

"Once Chris gets rolling with the visual stuff, he's very vivid and precise. It's impressive. He sent me a sketch the next day. I made some revisions and asked, "What's next?" He said, "Now I paint!" He goes from sketch to painting. No finished pencils or anything! Scary."

It took Chris about three weeks to paint Lady Kate's final, tragic war against the Vaylen

Copy Editing and Layout (April-May)

By April, we had signed on Johanna Novales (who, like Rich Forest, was another veteran from the Burning Wheel Revised project) to make the second copy editing pass. Once Rich finished his edits, Luke would input the corrections and send the sections to Johanna. I was finishing my first editing pass through the text at the time, so the full process had sections flowing from Luke to me, back to Luke, on to Rich, back to Luke again, on to Johanna, and then back to Luke a final time.

"Keeping up with the edits as they were rolling in was a daunting process. I almost lost it somewhere in there."

I finished my first edit near the end of the second week of April, and Rich and Johanna finished their copy editing passes not much later. I told Luke that I needed a few days to recharge my batteries, especially as my day job was getting busy, but that I would dive back in and begin my second pass through the text after he finished inputting Johanna's corrections.

Meanwhile, as Rich and Johanna were finishing up, Luke began putting together the finalized layout, placing the color artwork and sketches. This process had to wait until the end, because the images were to be associated with the text, and the text would move and change according to the edits.

"There's nothing worse than redoing 600 pages of layout!"

It was at this point that the money for the project began to run out. It appeared that Luke would either have to call in some of the loan promises he had secured, or he would have to return to work before the project was completed, putting a severe crimp in our schedule. Luke and I began discussing a strategy for a preorder that would help cover the printing costs. If he could cover one of the payments to the printer with a preorder, it would give him a little more flexibility on the budget front. Fortunately though, Burning Wheel was selling very strongly in this period. We were averaging sales of more than three books per day, a year after Burning Wheel had been released. When the sales numbers came in from our fulfillment houses (Key 20 and Indie Press Revolution), it was clear that the loans would not be necessary.

In the meantime, Chris was looking at a draft layout and loving what he saw. With the project nearing completion, Chris also managed to clear some more time in his schedule for us.

"After the cover was finished, Chris started doing more artwork for us. He did a couple dozen finished pencils for the book, mostly weapons and vehicles."

He also found the time to paint a cnidaria makara, the great, intelligent jellyfish that plied the waters of the Vaylen's original homeworld, the first species to be enslaved by the Vaylen and still the preferred host of the Yaadasahm clan. It's one of my favorite pieces in the book.

When we began the project, Luke had promised himself that each and every weapon and vehicle in the book would have an accompanying illustration. So when we had a few holes after laying out the chapter, he turned to Chris to sketch some additional pieces. Chris was very open to the work and did it incredibly quickly, even when Luke commissioned him to draw a brick for the improvised weapon entry. The piece is Luke's favorite in the book, and I believe he plans to buy the original from Chris and have it framed. I'm pretty sure he's the only person who's ever commissioned Chris to draw a brick.

Finally, as this whole phase of the process began to draw to a close, Luke and I began discussing ideas for the fiction introductions to each of the four lifepath chapters. We hashed out basic concepts and assigned two each to Sean Bosker and Rich Douek, who had supplied the fiction in Burning Wheel.

At this point we also saw the production dummy of the book from the printer, which was very exciting!

In the next part: The Weeks of Pain and Post Production

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Burning Empires: From Inception to Finished Product (Part III)

Shotgun Playtests (Dec.-Jan.)

Once Luke finished the initial rewrite of the Burning Wheel and moved on to the Character Burner, we began holding regular playtests of the various new mechanics during the evening at BWHQ. We’d sit down and set up a Firefight or burn Worlds, or even use the Infection mechanics to go through whole campaigns at the macro level of play.

The shotgun playtests were absolutely necessary, as they allowed us to very rapidly use the mechanics over and over again, time after time, to a degree that would take months or longer inside the framework of actual play. The tests were quite enjoyable at first, as we were still challenged with shaping the rules to conform to our vision of how they should work. But as time went on, it became less about the fun of creating rules and more about making sure that we were consistently getting the results we wanted. Without the investment of actual play and the connection to character and color that play engendered, it became tedious. Still, they were incredibly valuable, and the game would not be what it is without them.

These tests would often run late into the night, and I was consistently bleary-eyed walking into work the next morning.

Playtest Agra (January)

With the Character Burner rewritten, it was time to put together another playtest. Drozdal was off visiting family in Poland for the holiday, so we brought in Alexander to replace him.

This time we had a more fully formed World Burner to work with and actual lifepaths to use. We soon saw some of the things that were still missing from the lifepaths, but the lifepaths also gave us much better traction for understanding the setting we had created and also allowed us to use the Circles mechanics to greater advantage.

Additionally, we had now formalized something we did instinctively in Playtest Alpha: each character had to have a relationship with a figure of note on the other side of the conflict (i.e., with one of the GM’s antagonists). One of the things that had made us love the Iron Empires comics was how human the protagonists (and antagonists!) were. Sure, they were wrestling with the fate of their planet against an implacable foe, but they still loved, hated, committed adultery, etc. They were fighting to save humanity, but they were at the same time led astray by that which made them human. It really suggested the very core of Burning Empires play: the choice between doing what is necessary and pursuing one’s personal goals and desires. The first step in making that choice central to play was requiring that every player tie his character personally to the enemy in some fashion.

Now Burning Empires wasn’t just about fighting for the fate of the planet, it was about the fate of fathers, sons, sisters, husbands and lovers. And working to save one might mean sacrificing the other.

Agra also led to another key aspect of Burning Empires: scenes as currency.

One thing that Luke and I and others at the Forge have seen very clearly is that role playing texts in general are pretty poor at teaching players how to use them. Invariably, creators do things when running their games that are essential to making the games function as they should, and yet some of the most important of those things never make it into the text. We do things that are so ingrained that we take it completely for granted that other players, who learned to play in other environments, do them too. Once you release a game, if you interact with your fans, you quickly start to see patterns in the questions they ask. Pretty soon, the conclusion is inescapable: you’re doing something at your table that is not actually in the text. Burning Wheel is no different than other games in that regard.

Luke and I pledged that we would do our best to hard code the way we played into Burning Empires by critically evaluating every nuance of how we played our games, and making sure it made its way into the text.

During Playtest Alpha, Luke and I had watched very carefully what we and the other players were doing, how we went about involving each other and how we built toward conflicts. Just as importantly, we noted where things fell down and tried to understand what caused the failure. Luke synthesized it all and brought the new scene rules to the table for Playtest Agra. He had divided the things we did in play into four distinct types of interaction with the rules and each other. We used Color Scenes to allow our individual characters to take the spotlight and introduce cool details about the world that made the game a richer experience for all of us; we used Interstitial Scenes, which consisted of scenes of pure interaction between two or more characters; we used Building Scenes to lay the groundwork for conflicts, stuff like creating propaganda, buying technology or hacking a network; and we used Conflict Scenes for the serious action—big firefights and duels of wits.

Luke identified the different sorts of things we did when playing and broke them up into the above categories. Then he turned those scenes into currency by limiting their availability. In one Maneuver of the Infection rules (which equates to half a session or a full session of play, depending upon your speed of play), each player would have access to one Color scene and one Interstitial scene. Each player would also have access to one Building scene OR one Conflict scene. Additionally the players were guaranteed one Conflict scene, but could have a maximum of two in a Maneuver. The GM, also, had access to one Color scene and one Interstitial scene for each of his figures of note (he can have up to three), and one Building scene Or a Conflict scene per character. The GM was also guaranteed at least one Conflict scene and a maximum of two. Players could invite each other into their Interstitial and Building and Conflict scenes, as well.

“One of my design goals for Burning Empires was for this game to do what BW did not: BW does not enforce the structure of a story. You can sit around with BW and jerk off. I wanted to try to design a game in which the players HAD to tell a story. We accomplished that in two ways. One is the Infection mechanics (including the World Burner point totals). Knowing that the game is moving inevitably to an end encourages a narrative arc in play. It's an unconscious reaction—if there's an end, there's going to be a beginning and a middle. And those are the basic building blocks for a narrative story. The other commodity for enforcing the story is the scene structure. By preventing players from just sitting around and jerking off, we infused the game with a narrative pacing. You've got limited screen time. You've got to do SOMETHING. A little pressure like this went a long way to increasing the quality of player participation in the game. And it also had the necessary (and intentional) side effect of making the game feel like the comic books.”

We found that making scenes into a commodity created a very powerful dynamic in play. It really knit the group together. It made players shove the spotlight around, and created tremendous pressure to force the story/game forward with every scene. It also produced an unanticipated but very pleasant effect from interaction with the Advancement rules. Tests in Burning Wheel have always been a commodity, as they allow characters to improve, but the scene mechanics meant that which tests you chose to pursue during play became a very important consideration. It also made the opportunity to help your fellow players on a test much more valuable.

During this playtest, the Technology and Vehicles rules also took shape.

Once the first draft of Burning Empires was finished on January 9th, I began my first editorial pass through the text. At this stage, I was ignoring most grammatical considerations, focusing my attention on clarity and whether the mechanics worked. Most of my edits had to do with strengthening or better explaining particular mechanics, though I also included suggestions for new mechanics in certain instances.

Also, whenever writers are working something out as they write, they tend to write in the Passive Voice. It’s very common when you’re trying to explain something to yourself. Unfortunately, Passive Voice leads to incredibly convoluted sentences that can be very difficult to follow. So, many of my edits at this time also involved an attempt to eliminate uses of Passive Voice to make the text easier for readers to understand.

While I was working on the sections of text that Luke was sending my way, Luke spoke with Rich Forest about working as one of the copy editors on the project, making sure he could work within our deadlines.

As my edits came rolling in, Luke started going through the edits I had submitted and began redrafting the text. Once my edits had been incorporated, Luke began passing sections to Rich for a turn.

Moeller’s Three Sketchbooks Arrive (February)

By February, three sketchbooks of Chris’ work—everything he had done in the period leading up to and during his work on the Iron Empires—arrived at BWHQ. Aside from goggling at Chris’ sketches though, we were not yet ready to start dealing with the black & white art.

Luke was still working on trying to get Chris to do some original art for us, but Chris’ schedule remained far too tight. Getting nervous, Luke and I began discussing the possibility of bringing additional artists onto the project, a frightening prospect as Luke had not budgeted for such an expense. Luke also discussed the issue with Chris.

It was at this point that we received the most severe blow of the entire project, and one which led me, at least, to question whether we had played a very bad hand of cards when we decided to go forward with this project. Luke asked Chris for the original plates for the comics, to see what could be done to make them stretch to fit our needs for the project. And we learned that Chris did not have all of them.

As is apparently common among comic book artists, Chris had sold a number of the original plates to fans and collectors. And as the comics had initially been released in the 1990s, prior to the mass adoption of digital technology in the business, he did not have digital versions.

We turned to Dark Horse Books, which publishes the graphic novels, but though they were very easy to deal with and very professional, they had only a small archive of Chris’ work—mostly covers. They didn’t have what we needed.

Our choices were limited at that point. We were six months into the project and had a lot of time and sweat invested already. We’d have to make do with the plates that Chris had and try scanning the rest from the comics. Fingers crossed.

Wider Playtesting (Feb.-March)

Meanwhile, with Playtest Agra drawn to a close, we put together another group. Drozdal had returned from Poland, and Alexander had left us to put together an outside playtest group of his own. We had been playtesting with four players and a GM, so we thought it best to see what would happen with a larger group, especially in light of the scene mechanics. Our playtest group for Morelia consisted of Luke, Drozdal, Chris (not Moeller), Mayuran, John, Danny and myself.

Morelia was one of the most difficult worlds we played for several reasons. First, as we had suspected, the number of players made working with the scene mechanics a little difficult. We determined that four or five players were optimal for Burning Empires play. Also, I played a character that was ambivalent as to which side he was on, to see what would happen. It worked, but there was a great deal of tension at the table and between the group. It also happened to be a world that was thoroughly unbalanced in the Vaylen’s favor (we were playing the human side), and so we were steadily losing ground to the terror and turning to infighting as it happened. On the whole, the world worked, even though it was hard, and was a fascinating test.

While Morelia was under way, we had also sent the text to outside playtest groups. Alexander, Mike, Judd and Kevin all gamely gave it a go with our very roughly cut gem. Others, including the estimable Mike Holmes, agreed to read the text and comment. Several were not able to make it through an entire Phase, as outside commitments got in the way.

The rest, to our good fortune, had considerable difficulties. Giving your baby to someone else, and letting them sputter and founder with it, can be one of the most difficult things a game designer can face.

Luke can react very negatively when things seem to be going badly, especially when we get into this phase of a project and the strain starts to tell. Burning Empires was no exception. The initial playtest reports contained some very troublesome issues, and there were a few times when Luke was ready to give up as a result.

But the fact of the matter is that playtests that go wrong are by far the most rewarding. Few things will teach you more about your game’s weaknesses, and what is happening at your table that’s not in the text, than a troublesome and turbulent playtest session.

These months were very intensive in the development of Burning Empires, and the text evolved rapidly based on the input of the playtesters, Mike Holmes and my edits. Luke was releasing revised drafts nearly every week.

That, in itself, became somewhat of a problem. Due to the size of the text (it was a brick even then), few if any of the outside playtesters printed new copies of the rules from the revisions. Keeping track of who was playing with which revision, and whether the problems they were experiencing in play had already been dealt with in the up-to-date text, became increasingly difficult.

Finding a way to control that issue will be a priority in our next project.

It was also in this period that we finally settled on a name for the project: Burning Empires: The Iron Empires Forged on the Burning Wheel.

In the next part: Editing Phase I, The Art Comes Through, and Copy Editing and Layout

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Burning Empires: From Inception to Finished Product (Part II)

Continued from Part I

Drafting Ideas (Sept.-Oct.)

With the contracts well underway and our first high-level discussions begun, Luke spoke with his friend Bob and got his blessing for the project. Bob is one of Luke’s oldest friends and Luke considers Bob’s initial reactions a key part of his creative process. In this case, after Luke described his ideas for the Infection mechanics and Firefight, Bob told Luke he was nuts.

Generally, the more Luke’s friends are opposed to his mechanical ideas, the more driven he becomes to make them work. So Bob’s reaction was exactly what the project needed. Ultimately, Luke was so feverish in his description of his ideas that Bob told him to go for it.

With Bob’s blessing, it was time to get down to the grunt work. During this period, Luke was on the phone with Chris semiweekly, getting Chris to expand on setting concepts and the nature of Iron Empires society, and also trying to convince Chris to work on new original art for the game. He had some success with the former, but Chris’ regular work for DC Comics was keeping him too busy to do any additional work for us.

Vaylen

In the meantime, Luke and I began focusing on Vaylen culture, which we needed to understand before we could create any rules for them. Burning Wheel’s lifepath system, which we had decided to keep for Burning Empires, requires that you thoroughly understand the structure of a society in order to create lifepaths for it.

There wasn’t much to go on in the graphic novels, aside from talk of Vaylen ‘fingers’ in Faith Conquers and mention in Sheva’s War of Vaylen clans staking their wealth on attempts to colonize human worlds. Chris had some ideas to share about what the Vaylen were like, but largely we had to draw the few, disparate details into a cohesive whole.

First we had to answer the question: What does it mean, psychologically, to be a parasitic worm that can only gain sentience, memory and emotion by stealing the body and mind of another sentient creature? We decided that Vaylen don’t think of themselves as 'using' humanity. Instead, their leaders, the ones with human bodies, think of themselves as human. Their sentience is human. Their emotions are human. The memories they take from their hosts are human. If they leave their hosts, they lose sentience, emotion and memories (those that aren't encoded, anyway). If they enter a different host, the quality of their sentience, emotions and memories is different.

Vaylen desperately want to be human. And they want their children to be human.

But at the same time, they are creatures that gain sentience, emotions and memory all at once, in a split second of time. I imagine them as loving all emotion and sensation. At the same time, they do not have the direct experience that allows real humans to differentiate between good emotions and bad emotions, between good sensations and bad sensations.

The Ascetic that practices denial and restraint offers a path that is as interesting and sensation-ful as the Dilettante that pursues pleasures of all stripes. For instance, we gave the Dilettante the option of taking the Cannibal trait because the sensation of horror that emanates from the host when breaking that taboo is as delicious to the Vaylen as the sensation of sexual intercourse or drug-induced euphoria.

Once we had that concept, we had to explore the cultural ramifications of such a psychology. What happens to a society when one’s levels of intelligence and ability and depth of emotion are merely a matter of taking a new host? When a person that wants to experience childhood again simply has to take a child host?

What does it feel like to look upon your children in a tank and know that their capacity to experience is dependent on the bodies you secure for them? They can be animals or geniuses.

Then, for our own sense of closure, we had to satisfy ourselves as to why the Vaylen couldn’t simply clone human bodies to satisfy their needs.

Once we had answered all these questions, we were able to settle on a caste structure for Vaylen society, in which clans were regimented in the types of bodies they could own. Only the most powerful among the clans had access to human bodies. The rest had to make due with genetically engineered creations with less mental sophistication. Even better, we realized that the only way for members of less powerful clans to attain human bodies was to join a Vaylen finger (spies that infiltrate human planets). Perfect.

Luke began researching the Indian caste system and their system of familial power, and much of the feel of the Vaylen flowed from that research. He decided that the Vaylen needed to exist on two axes, the family and the caste. That way there could be internal tension, and they wouldn’t be a boring, monolithic alien culture.

Kerrn

The Kerrn were up next. In many ways, they proved more problematic for us. We only see one Kerrn in the graphic novels, but it’s clear that they’re intended as the ‘warrior’ aliens. While we really enjoyed the Kerrn Gopher in the comics, we frankly found the concept of ‘warrior’ aliens boring. They’re almost always some weird amalgam of Vikings and Samurai that I call Vikurai. Boring! We knew we had to do something different, while still upholding Chris’ vision for the Kerrn.

We started with what we knew from the graphic novels and Chris’ notes: The Kerrn were a genetically engineered slave race created by the Vaylen from human and plant genetic material. They looked like frogs, were capable of subsisting on photosynthesis, and were tough enough to withstand brief periods of vacuum. Somehow, a small group of Kerrn developed the ability to regain control of their consciousnesses and expel the worm from their bodies. The Kerrn fought a war with the Vaylen and won their freedom, fleeing to a hidden world. They would later join forces with humans and a select few would become the Emperor’s honor guard.

As with the Vaylen, we had to explore the psychology of genetically engineered slaves that won their freedom, and the cultural ramifications of that psychology. How would such unimaginable torment and horror shape a culture?

I pitched Luke on the idea of using Mossad as an inspiration for the Kerrn. Also, based on the narrative that we had, Luke had the idea that after their war with the Vaylen, the Kerrn crashed their damaged, stolen spaceships together and built a hidden, artificial world for themselves. Using that as inspiration, Luke decided to use the culture of submariners as an additional source of material for the Kerrn. The Kerrn would flow naturally from those roots in time.

Firefight, Psychology, Iron and Injury

Once we had a feel for the alien cultures, Luke began working on the Firefight rules. We knew that we wanted to base them on the Duel of Wits rules, and that each Firefight would have stakes. Firefights would not be simply about killing or being killed. That would happen regardless. They had to be about something. The early rules were very rough, but it was enough to allow us to begin a playtest.

We also began sketching out ideas for what Psychology (psychic powers akin to those described by Asimov in Second Foundation) would do, and how to translate that into mechanics. We spent a lot of time pouring over Sheva’s War, looking at the dialogue between Vienne, Sheva and Philippe, searching for clues as to what Chris’ psychologists could and couldn’t do. It was immediately clear that Psychology would be problematic. Psychologists have the ability to control minds. They can change Beliefs! How could we allow that sort of thing without turning Psychologist characters into generators of Social Contract dysfunction?

Luke had an answer: Connections. For most Psychology effects, a Psychologist would require a Connection. And we decided that our rules would not allow for a Connection to be forced upon a player. Instead, the Connection would be a player-to-player contract. A player of a psychologist could offer a Connection to any other character in the psychologist character’s presence. The player of the target character could accept or refuse, and that would be the end of the matter. Accepting the Connection would open the character up to a range of effects, both beneficial and deleterious. Most importantly, accepting the Connection would give the target character a FoRK die toward all social skills (including Persuasion, Oratory and Command) as long as the Connection was maintained.

We also created downsides to having too many Connections out as a psychologist: The more Connections you had, the lower your Barrier to incursion by other psychologists. To really give that teeth, we determined that a psychologist could not end a Connection on his own. He would have to request his Connection die back from the other player, who could then decide whether to give it back or keep it.

We believed these rules would ensure that psychologists had powerful juice, but that other players could use game-derived social pressure to keep abuses in check.

Luke also began putting together the rules for Iron (power armor) at this time, and we began to explore ideas for how we wanted Injury to work in Burning Empires. We explored the possibility of making all Injury trait-based, but eventually discarded the idea as too complicated within the Burning Wheel framework.

Playtest Alpha (November)

With a feel for the culture and some new mechanics to work with (but no lifepaths), we put together the first playtest group: Luke, Dro, Chris (not Moeller), Mayuran and myself. We created the world of Ogun using the new World Burner, but still had to use the Burning Wheel lifepaths to come up with analogs of the types of characters we wanted. Drozdal decided to play a Kerrn, and Luke had him use the dwarf lifepaths to simulate it. He would complain mightily about it in true Polish manner in the weeks to come.

While there wasn’t much of Burning Empires yet in place, this game really showed us the types of things that players would want to do in Burning Empires. We learned very quickly what sorts of things our rules did not cover. It also showed us what the new Lifepaths of Man would require, both structurally and in terms of skills.

The initial Technology rules began to take shape at this point. We didn’t yet know exactly how we intended to handle them, but knew that we wanted players to be able to talk tech into existence.

Based on the six sessions of the playtest, Luke revised the Infection, World Burner and Firefight mechanics.

Luke Carves Up the Burning Wheel (Nov.-Dec.)

As the playtest was getting underway, Luke was also beginning to plan the physical design of the book. The very first step Luke takes when designing a project (before logos, layout, etc.) is to select fonts.

“Fonts are the foundation for the look of a book. They’ve got to knit together all the other elements. So for BE, I knew I wanted a different look than BW. It had to have a classic look to it, like BW, but also had to be modern.”

Luke went through his font database of several thousand fonts and made a short list of the fonts that suited his needs. He knew he’d need four fonts: body copy, chapter header, subheads and example copy.

His first selection was ITC Tiepolo.

“I selected Tiepolo for the body because it’s a semi-serif with very shapely letters, but very unobtrusive, and it benefits from looking both modern and classic at once.”

He selected Europa for the subheads in order to mimic the covers of the graphic novels. Caliban, for the example copy, made the transition from Burning Wheel.

“Caliban stayed on from BW because it was convenient and it linked the new text with BW, which was serendipitous because later Caliban fit nicely with the layout concept of the future computer from the past.”

The final selection was Democratica, which had a very mechanical look, as the script font for the titles. However, Luke soon realized that Democratica had been used in a number of other RPGs. Luke believes that fonts make people who see them form strong subconscious connotations. He didn’t want readers to mentally connect Burning Empires with those other RPGs, so he chose a new font: Oxford. Luke felt Oxford wound up being the better choice, as it would fit better with the eventual design concept of the book.

Arguments

With font selection out of the way, Luke and I started holding the first of many (sometimes heated!) discussions of the best way to present the information in the new book. Burning Wheel consisted of two books, allowing us to send new readers from one to the other in a manner suited to learning the rules, while also keeping the information compartmentalized in a way that made it easier for reference in play. But Burning Empires would be a single book. We had to decide upon a structure that would give it a logical flow to a new user while still being easy to reference.

The most important decision at this point was that the World Burner had to precede the Character Burner. Our conceit was that players would not be able to burn their characters until they had collaboratively created a world. We would later reinforce that mechanically.

“The World Burner to Character Burner decision was huge. It shaped the rest of the game. We knew that we wanted the players to be able to add their own stamp to the setting via the World Burner. We knew that from the beginning. But I don't think we understood what that meant for the rest of the game. Not until I physically put that chapter in the beginning of the book did we truly see that your choices when building your setting affected everything else about the game you were about to play, from your Lifepath choices, to the maps you were going to draw in Firefight!”

We also decided the Character Burner would precede the Burning Wheel itself, and the order of the lifepath chapters and all the chapters in the Burning Wheel section. The latter would not remain static, as chapters would move, merge or disappear entirely based on our play experiences in the coming months.

Grunt Work

Once the structure had been determined, Luke set to work. He rewrote the Burning Wheel in November, excising chapters that were no longer needed (Fight!, Range and Cover, Sorcery, Emotional Magic, etc.), and incorporating our new material. He then set to work on the Character Burner in December, pulling together the Human, Vaylen, Kerrn and Mukhadish lifepaths, the new skill list, and the new trait list. The skill list chapter and the trait list chapter, as always, were some of the hardest, most painful chapters to write. Luke, who is incredibly driven when working, pushed through and completed the first draft of Burning Empires by January.

In the next part: Shotgun Playtests, Playtest Agra, Moeller’s Three Sketchbooks Arrive, and Wider Playtesting

Tuesday, July 25, 2006

Burning Empires: From Inception to Finished Product (Part I)

Last week I posted about Brennan’s description of his process for writing Mortal Coil, and promised that I would give Burning Empires a similar treatment. Well, here’s where I start to deliver. It was such a long, intense process (I’ve been gathering notes and consulting with Luke about it for the past two days) that I’ve decided I need to break it down into multiple posts. What follows is a description of the very first steps we took.

It All Starts with Jihad

The story of the Burning Empires project actually began with Burning Sands: Jihad, the Dune-inspired space opera supplement for Burning Wheel.

Jihad was our love letter to Burning Wheel fans, a thank you for all their support. It was also the first real collaborative project at BWHQ. I wrote the World Burner, Drozdal was the mad scientist behind the Black Market rules, and Luke did all the other heavy lifting, though Dro and I came up with some of the lifepaths and traits.

To Luke, the success of such a collaborative project was fundamental to going ahead with the Burning Empires project.

“The reason the collaborative nature of Jihad was so important is that I knew the BE book would be big and stressful and would require some serious effort from you [Thor] and Dro. I don't know if I would have taken on the project without the knowledge that we could work together. Or, if I did take it on, it probably would have been a disaster.”

Jihad got a very warm reception from our fans when we released it just prior to Gen Con, despite the fact that we had kept it under wraps until it was done. We were very pleased with the results. Dro and Luke started talking wistfully of giving Chris Moeller’s Iron Empires (recently re-released) the same treatment.

Meanwhile, the playtest group I’d put together for the Jihad project was still going strong, and I was very pleased with where the Propaganda War rules were taking us. As we discussed the play results over lunch at Dosa Hut, our favorite South Indian vegetarian restaurant, Luke and I were also tossing around the idea of a more robust and rigorous treatment of those rules.

On a whim at the end of August, after we’d returned from Gen Con, Luke decided to send Chris an email about the possibility of doing Iron Empires as a role playing game. Fortuitously, Chris had recently decided that an attempt to do the Iron Empires as a role playing game with another company wasn’t going to go anywhere, and he was going to shop it around to a smaller company that was excited about the property.

We’d just come off a fun and very successful Gen Con, and were seriously discussing setting out in a new direction with our designs. However, once Chris showed interest in pursuing an Iron Empires project with us, Luke decided that we needed to strike while the opportunity was available. Luke convinced me (grudgingly!) that we needed to put the project on which we were now focused on the back burner and turn our attention to the Iron Empires.

Legal Matters (Aug.-Oct.)

Chris and Luke consulted their lawyers and Chris’ agent, and spent August to October hammering out a contract. Our lawyer advised us against doing a licensed product, but we stubbornly felt the advantages and opportunity to work with Chris Moeller outweighed the risks.

The legal process was made far simpler than it might otherwise have been, as Chris owns all the rights to the Iron Empires and Luke owns all the rights to Burning Wheel. Still, the contract had to make clear that Chris retained his intellectual property and Luke retained his, whether the project was completed or not. The final contract specified that Chris would retain ownership of all setting material, even material created by us as part of the design process, while Luke would retain ownership of all mechanics, even those designed specifically for this game. It was also necessary to nail down how costs and revenues would be allocated, and what Chris and Luke’s responsibilities were. Chris agreed to supply all the color art from the comics, as well as several spot pieces and the cover for the game.

But the real sticking point contract-wise was final approval for content. Recognizing that our production timeline would not allow for any delays caused by approvals (as we have seen with multiple licensed RPGs in the past few years), we were loath to give away final approval. Nor were we much entranced by the possibility of having to compromise our creative vision for the project. At the same time, we recognized that Chris had an equal interest in protecting his setting.

In the end, contrary to our lawyer’s advice, Luke agreed to give Chris final approval. Under the conditions of the contract, Luke was obligated to submit material to Chris. However, the contract also stipulated that Chris had three days from the material’s submission to request changes, after which final approval for that material reverted to Luke.

Research and Meetings (Sept.-Nov.)

With the legal process underway, Luke, Drozdal and I began to put together our game plan in September. We held a series of meetings to nail down the core concepts for the game. The first thing we settled upon was that the underlying metaphor for the game would be disease. The Vaylen were a parasitic infestation infecting the bloated, dying body of humanity. Once we had that concept down and had a chance to explore the ways in which we could extend that metaphor throughout the game, we began putting together the initial World Burner questions and numbers and rudimentary Infection mechanics (based on Jihad’s Propaganda War and informed by that mechanic’s strengths and weaknesses in play).

Meanwhile, Luke started investigating printing options. He knew right away that he wanted the book to be digest sized, full color and hard backed, with a traditional print run. With that in mind, Luke contacted several colleagues who had recently printed full color, hard backed RPGs to gather information about printers and quotes. Armed with that information, Luke then approached several printers for direct quotes on the project.

Far and away, the best quotes for a project like ours came from companies based in China. In fact, the US printers cost about twice as much for color offset printing. It was not exactly what we wanted to hear. Luke had decided that he was willing to pay a premium not to print in a country with poor labor protections and a history of human rights abuses, but the reality was stark: We would not be able to produce a profitable RPG that met our production values without printing in China.

The project almost died right there. But the opportunity to work with Chris Moeller and have access to that much beautiful, color art doesn’t come along every day. We decided to press forward.

Luke settled upon Hong Kong-based Regent Publishing, which conveniently has an office in New York, and met formally with its representative, Robert Conte, on November 15th. Robert gave Luke the contracts and they discussed the timeline for production. Regent has published numerous RPGs and was familiar with the product. Robert even asked Luke if we needed to have the book ready by Gen Con.

The contract with Regent was soon settled, though our lawyer had advised us against printing in China. Aside from ethical consideration, he also noted that we would have difficulty seeking recourse if anything should go wrong. A great deal more nervous than we had been, we continued on.

Research was a major part of this phase of the process. In addition to rereading the graphic novels and notes with which Chris had supplied us, we read as much SF as we could get our hands on, especially stuff that is considered canonical. We paid special attention to Isaac Asimov’s Foundation novels, as we saw them as ‘foundational’ (sorry) to Chris’ work and they also rank among our favorites. The research materials were passed freely among the BWHQ crew and most of it found its way into the ‘Ography.

As an interesting side note, playtesters who had not read the graphic novels were not allowed to read them during playtesting. We focused them on the game and their virgin impressions of it, as we didn’t want them inadvertently filling in details that weren’t there.

Luke also sought and secured loan promises from friends at this point. Although the loans never became necessary, the promises were key in allowing the project to move forward. Luke had just been laid-off from his job and had made the decision to live off his savings until the project was completed, allowing him to work on it full-time. The loan promises gave him the confidence to do that, rather than immediately seek another job.

In the next part: Drafting Ideas, Playtest Alpha, and Luke Carves Up the Burning Wheel

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Brennan Offers a Look Inside the Process of Creating Mortal Coil

If you've already created a game, care to share a little about your process? I'll do my best to get something together about the Burning Empires process in the next few days.

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

The Value of Creating Scenarios for Your Game

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

Genre Conventions and Definitions

Without putting too many words in their mouths, I think I can sum up the bare bones of their arguments as follows:

- Jon believes that Sci-Fi color is all that is required to make a game Sci-Fi.

- Joshua is taking the stance that SF (quoting from a post of his at Story Games) "is a genre in which human conflicts take place that can only happen in the environment of the story."

Interestingly, I think Burning Empires can straddle the divide and come down on either side depending on the priorities of the players. By default, Burning Empires is a space opera game, which would align it with Jon's Sci-Fi argument (as Guy noted, Star Wars is a fantasy, not science fiction, unless you accept the Sci-Fi argument).

On the other hand, the World Burner and Technology Burner allow Burning Empires players to focus on how particular technologies and environments might affect human conflicts, if that interests them.

Joshua's Shock:, on the other hand, is designed to provide a laser focus on that particular type of story.

So, with that as a primer, let's open this topic up for discussion. We don't need to restrict ourselves to science fiction either. Feel free to discuss what it is that is essential to establish a particular genre, and why.

Monday, July 10, 2006

Burning Empires Approval Copies

The approval copies for Burning Empires came in last week!

Man are they gorgeous! And hefty.

I can't wait to see people flip through this beast at GenCon.